- HOME

- INVENTORY

- GALLERY

- BOOKS

- CATALOGS

- ABOUT & MORE

- CONTACT

Contact Us

Steven S. Powers | Joshua Lowenfels Gallery

53 Stanton Street, New York, NY 10002 | 917.518.0809

Steven S. Powers and Joshua Lowenfels have a shared gallery on the Lower East Side at 53 Stanton Street. We exhibit a Venn diagram of Outsider, Self-Taught & Contemporary Works of Art. We are three minutes from The New Museum, and 70 other galleries on the Lower East Side.

HOURS: Thursday - Sunday, 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm or by appointment.

Getting here is easy. Located near the New Museum, 53 Stanton Street is 1 block south of Houston between Forysth & Eldridge. Take the F subway to the 2nd Ave stop, or the J / Z to Bowery - then it's a short walk.

ALL OBJECTS ARE GUARANTEED AS REPRESENTED.

Current Exhibit:

Dog Days on Stanton Street

July 10 - August 30

CLICK HERE for price list.

CLICK HERE to see an Instagram Reel discussing this exhibit.

Dog Days on Stanton Street:

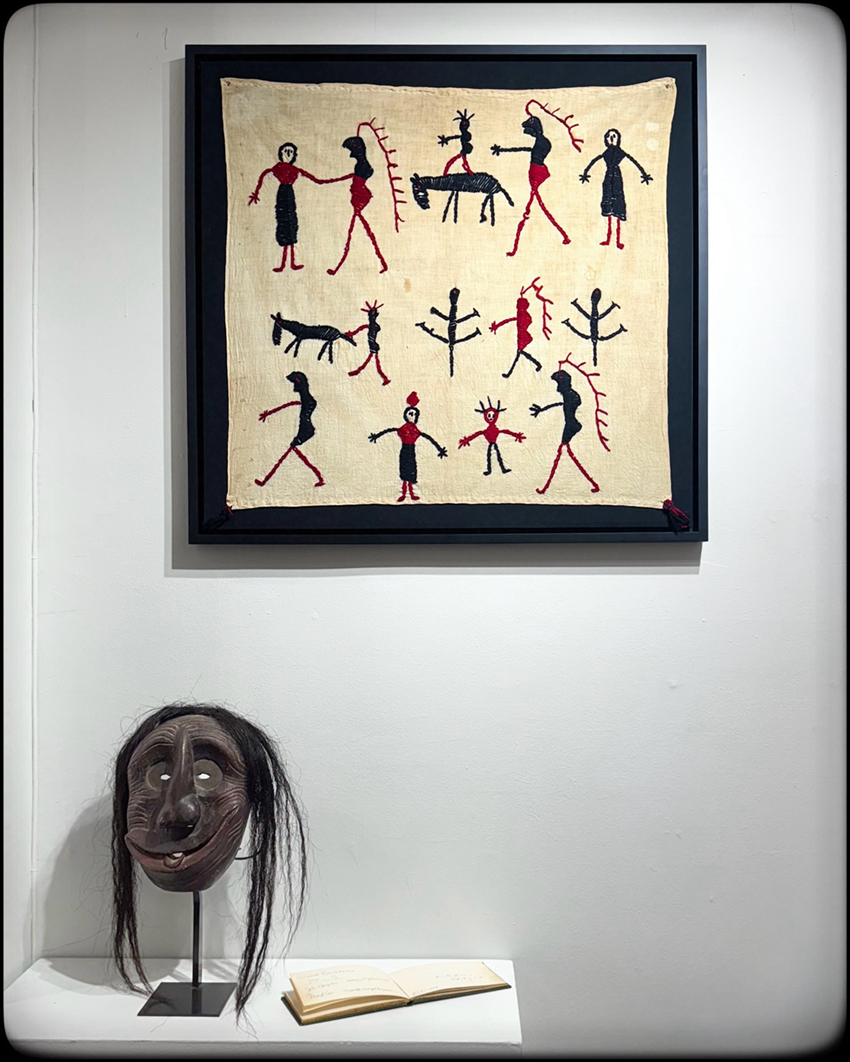

Summer is heating up, and our mascot is feeling the heat of the concrete jungle. Our summer exhibit features an exciting mix of recent acquisitions and discoveries, including mid-century paintings by “A. Dill” (Delaware River - Bowman’s Hill Tower), several works by the African American preacher/painter Reverend Joel Hewlett (1921-1994), striking portraits by the Italian farmer Pietro Ghizzardi (1904-1986), powerful African American and Native American textiles, an Atomic-Age Adventist Polemic, works by Vincent Smith (1929-2003), Nat Werner (1908-1991), Sal Salandra (1946-), and exceptional examples of Black Folk Art with additional surprises. July 10 - August 30.

Please visit the gallery to view this special exhibit, on display through August 30.

Past Exhibits:

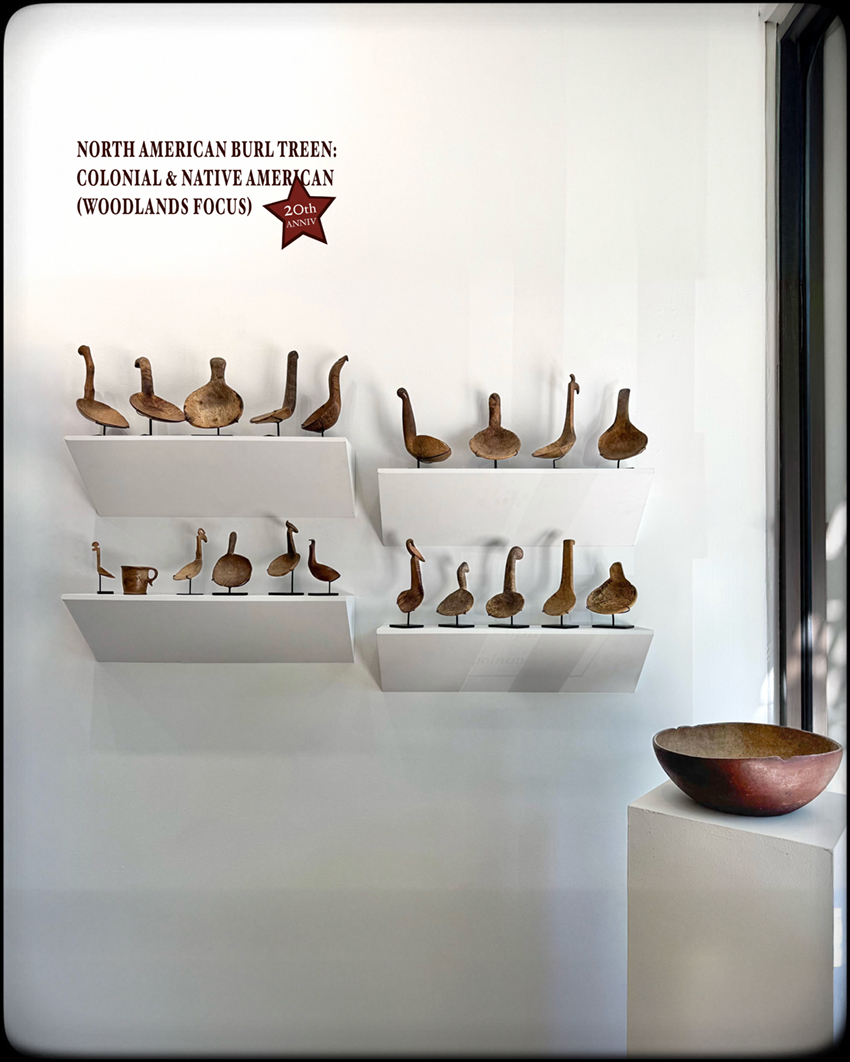

North American Burl Treen: Colonial & Native American (Woodlands Focus)

Through July 6th

CLICK HERE to see an Instagram Reel discussing this exhibit.

As Sir Paul sang, “It was 20 years ago today.” Well, not to the day, but in the spring of 2005, my book, North American Burl Treen: Colonial and Native American, was published. It was and still is the only substantial study of this cross-cultural art and craft. In recognition, we are having a small exhibit of burl treen and other treen at the gallery.

The exhibit focuses mainly on Woodlands burl and effigy ladles (many of which are featured in the book), a few Woodlands bowls, a masterpiece Delaware speaker’s staff, and a remarkable Colonial American ash burl basin (which is my favorite turned piece in the book).

I have always said that if I were not a dealer, I would collect Woodlands effigy ladles. They go well beyond utility and serve as platforms for sublime, soulful, and small-scale sculptures.

The Woodlands people’s diet was typically stew-based, and they used personalized eating ladles that held a totemistic or special meaning for the owner, which were usually made in consultation with a medicine man or elder.

Ash burl ladles without effigies were primarily food preparation utensils and thus developed complex surfaces from daily use.

Please visit the gallery to view this special exhibit, on display through July 6th.

December 5 - January 19, 2025

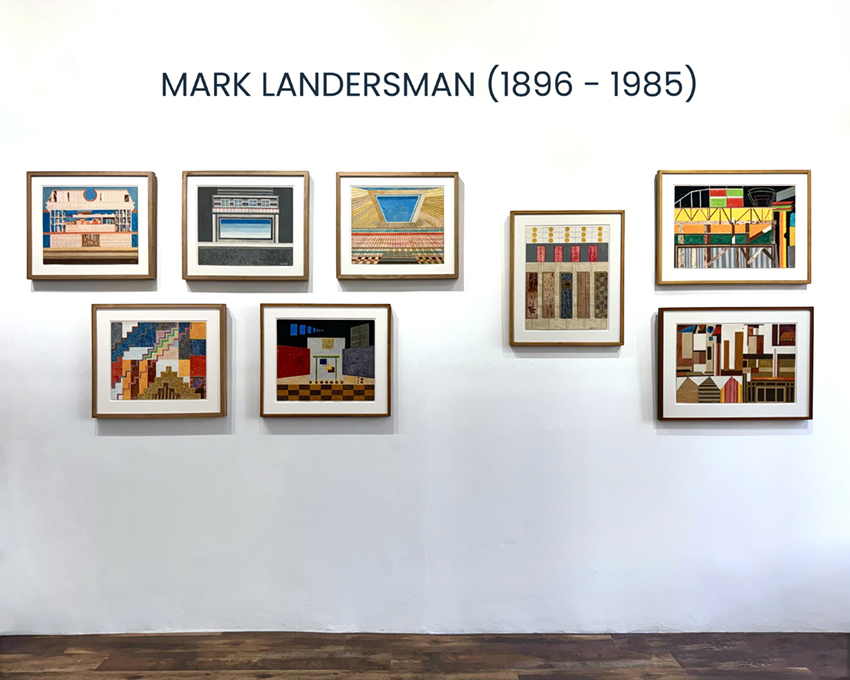

Mark Landersman (1896 - 1985) with Selections From Our InventoryAs part of our new exhibit, we are pleased to introduce the discovery of paintings by Mark Landersman (Brooklyn, NY, 1896-1985), a career garment worker and self-taught artist. Recent finds include a remarkable self-portrait of an unknown African American artist dating from the 1960s and “The Wilton Madonna,” a concrete sculpture formerly of the Peter Brams Collection. The exhibit will be up from December 5 to January 12, 2025.

Mark Landersman was born into a Jewish immigrant family in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. His mother was related to Boris Thomashevsky (star of Yiddish theatre), and his father trained as an architect. However, despite his father’s formal education, he and his family worked in the garment industry like many Jewish immigrants when they arrived in America.

Mark married Pearl Antonier, worked in the garment industry, and became a buyer, merchandiser, and creator of design concepts.

In 1954, Mark began painting with gouache while recuperating from an operation. Over the next 30 years, Landersman experimented with abstract and representational paintings while continuing to work in the garment industry until his retirement at the age of 80. He continued to paint until his death at 89.

The works herein are his most original and abstract. He combines complex patterning and structures with inventive architecture—they appear to be informed by the lights, energy, and pace of the commute between Brooklyn and Manhattan. One cannot help but relate these to his father’s lost profession.

For Landersman, these were a private pursuit, and he never sought to show or sell them. To this end, these works have never been seen outside the family until now.

October 17 - November 30, 2024

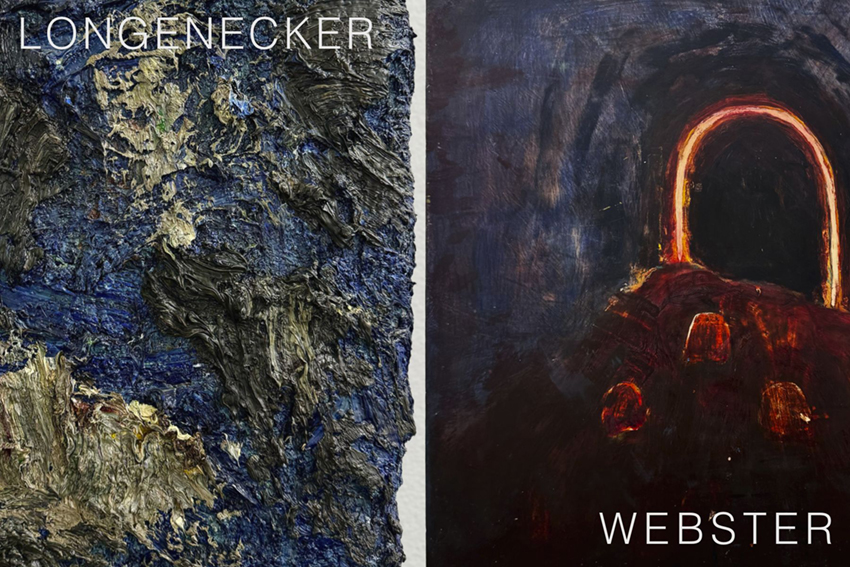

Fat Over Lean:

Joel Longenecker | Chuck Webster*Artists reception October 17, 6-8pm

CLICK HERE for the press release.

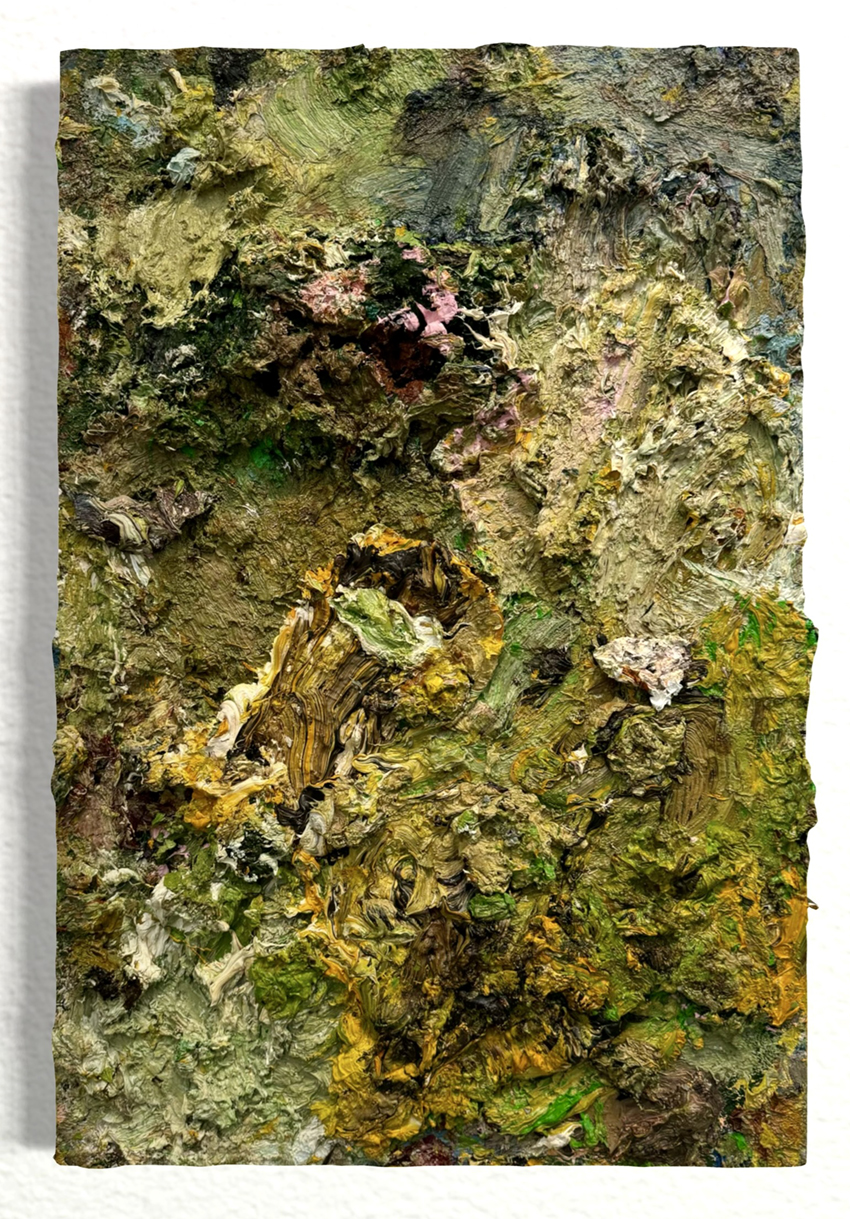

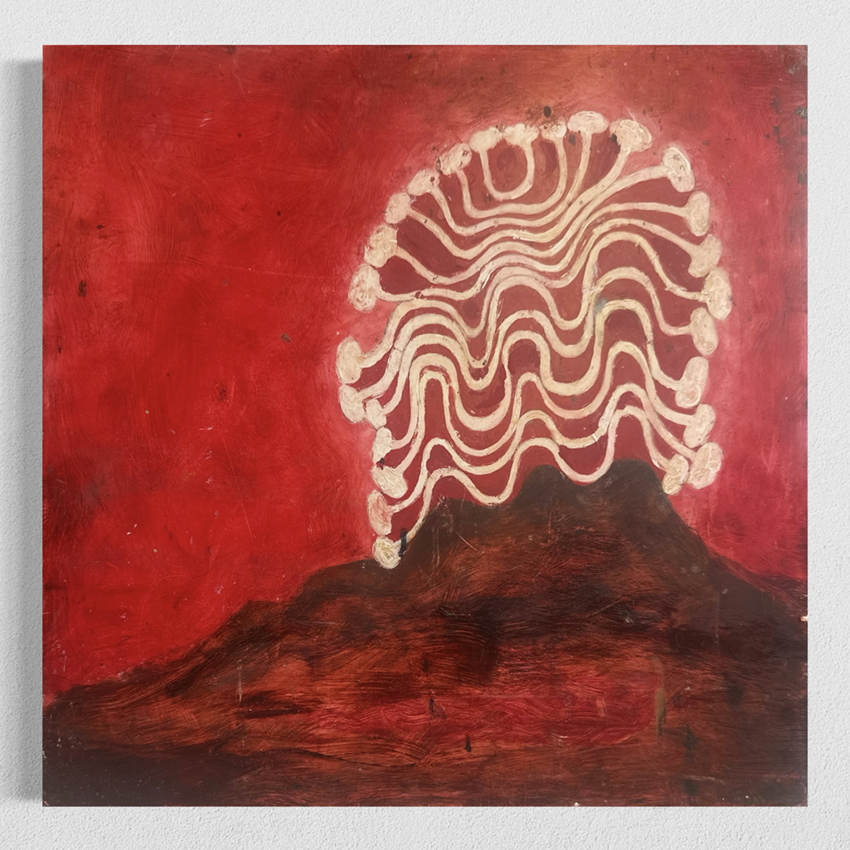

CLICK HERE for price list."Fat over lean" is a centuries-old painter's proverb referring to best practices within oil painting. Joel Longenecker and Chuck Webster are enamored with the malleable qualities of oil paint. Within their work, they incidentally record the hours, days, months, and sometimes years they put into a single work—Joel more with the addition of paint and Chuck with subtraction. Figuratively speaking, Joel's are "fat," and Chuck's are "lean." Joel's accumulate paint, like sedimentary layers of the earth, while Chuck's show erosion with erasure and cover-up. They both create a complex depth within their work—like they could be part of a larger universe or things we find under intense scrutiny.

Joel Longenecker’s work looks like shovel-ripped sod containing layers of earth. Longenecker states that “they are constructed much like the earth’s strata, from the deepest layer (the bedrock) up to the surface (the soft topsoil). Each layer consumes and buries the preceding one”. The art critic Lilly Wei wrote that Longenecker “scrapes down [semi-dried paint] so the soft inside, like wet clay, remains. This scumbled field provides resistance for his next layers as he traverses his field, repeating the process, sparring with the grit and goo, the hard and the soft”.

Longenecker lives and works in New York and has been exhibiting for over thirty years and has been reviewed and written about extensively.

Chuck Webster is also deeply engaged with the creative process through layering, glazing, sanding, adding, and subtracting paint while blurring the lines between painting and drawing. Yet, this earnest approach is loosened by his sense of humor, nostalgia, mood, mystery, and pop culture awareness. This survey of paintings spanning over twenty-five years shows abstract compositions hinting at some other world. Through his meticulous approach to detail, we see something familiar that we think we know yet can’t quite put our finger on.

Art critic Roberta Smith of the New York Times described Webster’s work as “little big paintings,” stating that “they have a strange, irrepressible scale, a largeness that exceeds their size and creates a distinctive, slightly comedic sense of intimacy.”

Webster lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. His work is in numerous public and private collections, including the the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Webster has been reviewed in the New York Times, Hyperallergic, The Brooklyn Rail, and Art in America.

September 5 - October 12, 2024

Dealer's Choice: Full House

Recent Acquistions & Highlights

From Our CollectionsOur fall exhibit, Dealer's Choice: Full House, features new acquisitions and personal favorites from our collections, like an early 20th-century Bee Keeper's Mask/Hood or a New York Post embroidered pillow by Andy Warhol's bestie Brigid Berlin.

Personal favorites include an important African American appliquéd textile, an incised carved and painted house portrait by the "Checkerboard Artist," an exceptional 19th-century African American doll, a substantial work by North Carolinian Outsider Artist Leroy Person, and a tout made from painted tires and carved wood.

Other works in the exhibit are an early work by Coenties Slip artist Jack Youngerman (1926-2020), an asylum period painting by Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919), a mysterious midnight painting by early San Franciscan artist Eva Withrow (1858-1928), a beautiful Minnie Evans (1892-1987), a stunning Edwin Lawson (1911-1980), a masterwork by Henry Dousa (1820-1903?), two male nude wood constructions by Charles Jarm (1932-2021), an extremely early Philadelphia asylum watercolor, ("painted by a maniac") by Richard Nisbett (1753-1823), two egg hatching stone carvings by James W. Washington, Jr. (1909-2000), an early ceramic creature by Japanese nonverbal artist Shinichi Sawada (b.1982), ceramic vessels by The Mad Potter of Biloxi, George Ohr (1857-1918) and mind-blowing works by sand artist John A. Adams (1891-1967).

Additionally, for the first time at the gallery, an important and historically unique miniature portrait of Benjamin Franklin, done by Joseph-Aignan Sigaud de Lafond (1730-1810) created by an "electric spark," is on display.

And since one of our favorite artists is "anonymous," there are several stellar works by unknown artists.

This is an exhibition not to be missed!

April 11, 2024 - May 18, 2024

BADGE OF COURAGE

MARCIA GOLDENSTEIN: WOMEN IN STITCHES

& THE VERNACULAR ID BADGE: AMERICAN WORKERS IN THE AGE OF UNIONS.*Artist reception/book signing April 11, 6-8pm

CLICK HERE for the press release.

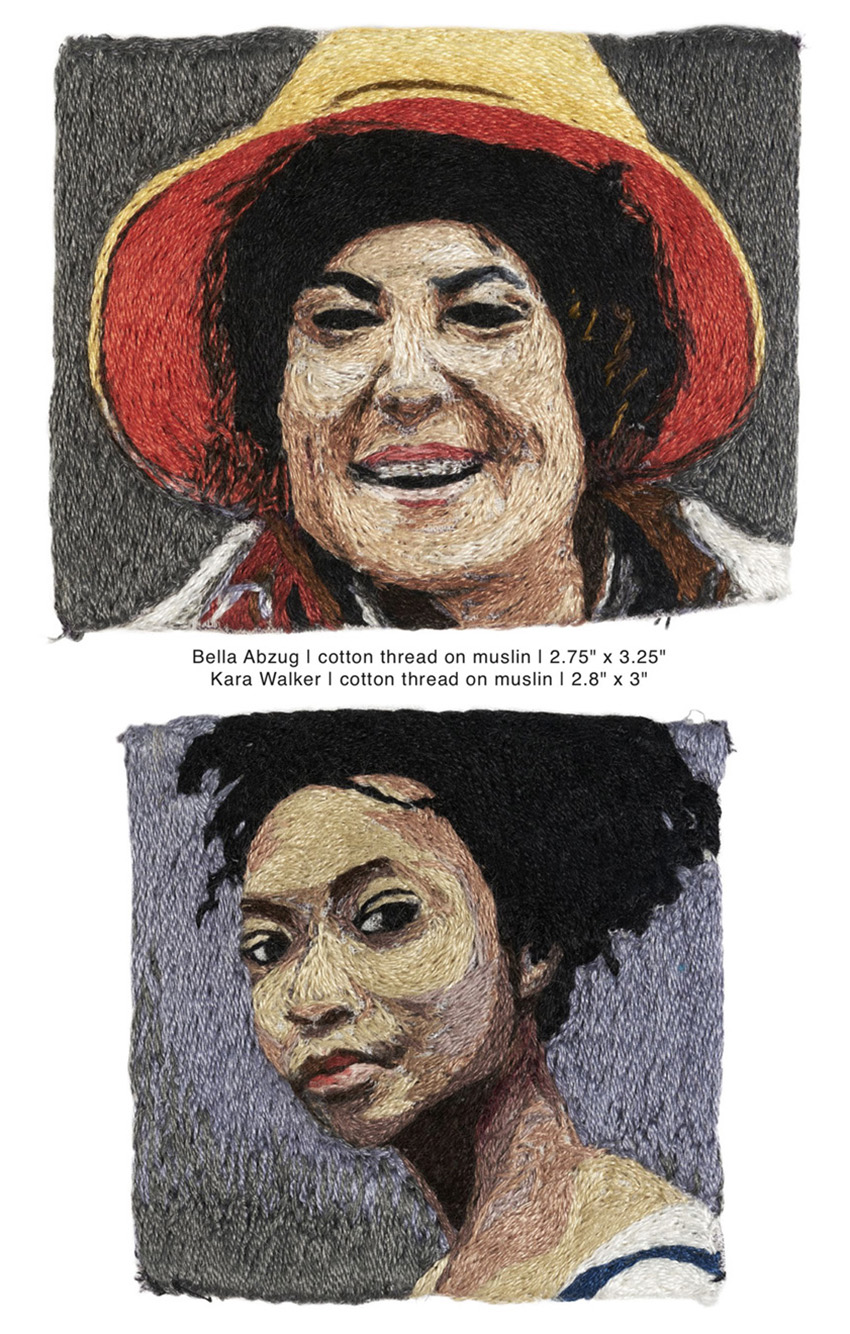

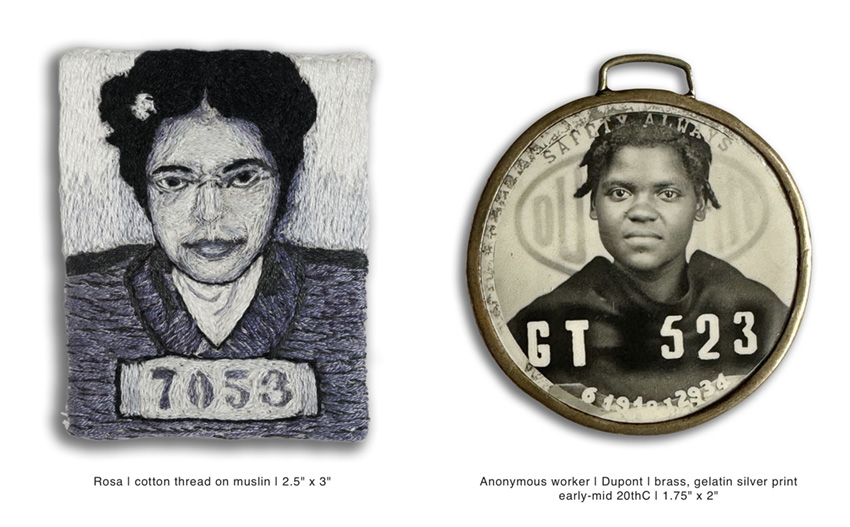

CLICK HERE for price list.This exhibition explores labor through the physical act of creating an exhaustive series of embroideries by our artist Marcia Goldenstein, her subjects' dedications to their visions and advocacy, and an extensive collection of vintage employee identification badges.

Over the last 15 years, Goldenstein has wrought two bodies of work venerating female artists and activists. Combining her professional experience as a painter with embroidery, Marcia builds up an image, much as she would a painting—stitching colored cotton threads to create complex tonal gradients and deep textures like paint and impasto.

Like Anni Albers and Lenore Tawney, Goldenstein has taken what was once considered "women's work" and elevated it beyond craft. With the "Artist Series," Marcia represents the past by working in black and white, embroidering deceased female artists often left out of art history. The "Activist Series" uses color for women of the near past and present who use their voice, art, poetry, and politics to help make a positive and progressive change in the world.

Goldenstein has exhibited these works at multiple museums; however, this is their first gallery exhibit.

The post-it-sized embroidered portraits play well off the vernacular photography of the vintage metal and enameled badges that house portraits of the Everyman/woman workers from when a third of the country held union jobs. These unions were inextricably linked to the growth of the middle class and instrumental in advancing civil rights and policies that addressed gender-based discrimination.

The badges are surprisingly satisfying in hand—they have good weight, and one cannot help but wonder about the individuals pictured. Most of them are assuredly dead; however, several may still be alive—where are they now? What happened to the young sailor on the Pearl Harbor badge? We recognize some companies, such as Campbell Soup, Goodyear Tires, Frigidaire, and Heywood-Wakefield, but what happened to the Blood Brothers Machine Company or Frankoweave Incorporated?

These enameled badges that bear a swath of humanity serve as an ad hoc timeline of labor through The Roaring Twenties, The Great Depression, WWI - WWII, and the dawn of the Civil Rights Era.

July 13 - September 17, 2023

Picnic: Lett-Haines | George Ohr & MoreCLICK HERE for Lett-Haines / Ohr price list

CLICK HERE for press releaseSteven S. Powers and Joshua Lowenfels present, Picnic: Lett-Haines | George Ohr & More. The nucleus of the exhibit centers around a rare collection of sculptural works by British artist Arthur Lett-Haines (1894-1978) and a select grouping of pottery by American master George E. Ohr (1857-1918). Picnic will have an opening reception on July 13 from 6:00-800pm and run through the summer until September 17.

Lett-Haines was an English painter and sculptor who, along with his lifelong partner, Cedric Morris, co-founded the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing (also known as Benton End), whose students included Lucian Freud, David Carr, and Maggi Hambling. Lett-Haines was known as the "father and facilitator" of the school, and along with numerous tasks between critiquing student works and administrating, he prepared two meals a day. In the early 1960s, he started creating small personal sculptures ("humbles"), which he assembled from food waste like animal bones, fruit skins, and plant matter. Then he combined these with other found materials like tobacco tins and aluminum flashing to create odd, quirky, fantastic creatures and objet.

As we have Lett-Hanes for the picnic "meal," George E. Ohr sets the "table." Ohr, widely known as the "Mad Potter of Biloxi," was a remarkable artist whose innovative pottery approach challenged his time's conventions. His journey as an artist eventually led him to become the most influential figure in American ceramics. Ohr's artistic legacy extends far beyond his pottery—his daring and unorthodox approach to art continues to inspire contemporary artists. Among George Ohr's works are a couple of his desirable snake mugs, a bisque-fired pot with reference to the New Orleans newspaper, The Times-Democrat, and a rare and unusual match holder featuring the figure of a Brownie.

In addition to the core of the exhibition centered around Lett-Haines and Ohr, the theme of 'picnic' is complemented with additional works by Jack Youngerman, Nellie Mae Rowe, Ralph Albert Blakelock, Sanford Wurmfeld, R. E. Treubel, and a large selection of related paintings and sculpture by artists known and unknown.

Picnic: Lett-Haines | George Ohr & More runs from July 13 through September 17, 2023.

November 25 - January 15, 2023

Herald Nix & Roger Brouard: Gilded SplintersCLICK HERE for Herald Nix price list

CLICK HERE for Roger Brouard price list

CLICK HERE for press releaseHerald Nix & Roger Brouard: Gilded Splinters. Nix and Brouard embrace the process—the journey as much as the destination. Finding and creating routes, acknowledging missteps along the way, and evidencing them as part of the finished work. They are interested in finding something new within something familiar, as we can often find more within boundaries than without.

Nix (b. 1951) makes daily trips to nearby Shuswap Lake, British Columbia, and uses the familiar landscape as a template for much of his work. Having the broad subject already set allows for the improvisation of oil paint onto his birch panel—an extemporaneous creation within a framework. Brushing, scraping, pushing impasto, and paint thinned out so that it seeps into the wood grain of the panel. Because Nix focuses on what develops on the board in front of him, he takes peripheral inspiration from the lake's air, light, and weather rather than faithfully recording the landscape. It is why his works always look fresh and remarkably never redundant.

On long flights to China, Brouard (b. 1946) would ink ideas for sculpture yet realized. The drawings are quietly mesmerizing—heavy, black sketchy lines, often with wite-out corrections and a keen sense of balance. Brouard is a master carpenter, but for his sculpture, he uses a saw as he uses a pen—his black-painted, cut plywood forms often have splintered edges and putty at the joints, similar to his inked jagged lines and wite-out drawings. His line has a hesitant fluidity—it is not effortlessly smooth—it allows us to see the process.

Nix and Brouard both had professional lives outside of their artistic pursuits. It's not that art came later in life; it was always with them and helped with their professional objectives, Nix as a celebrated musician and Brouard as a carpenter and entrepreneur. It is only now that life has come to their art and has afforded them this time of more sustained focus.

We are honored to pair these artists in their inaugural New York exhibits.

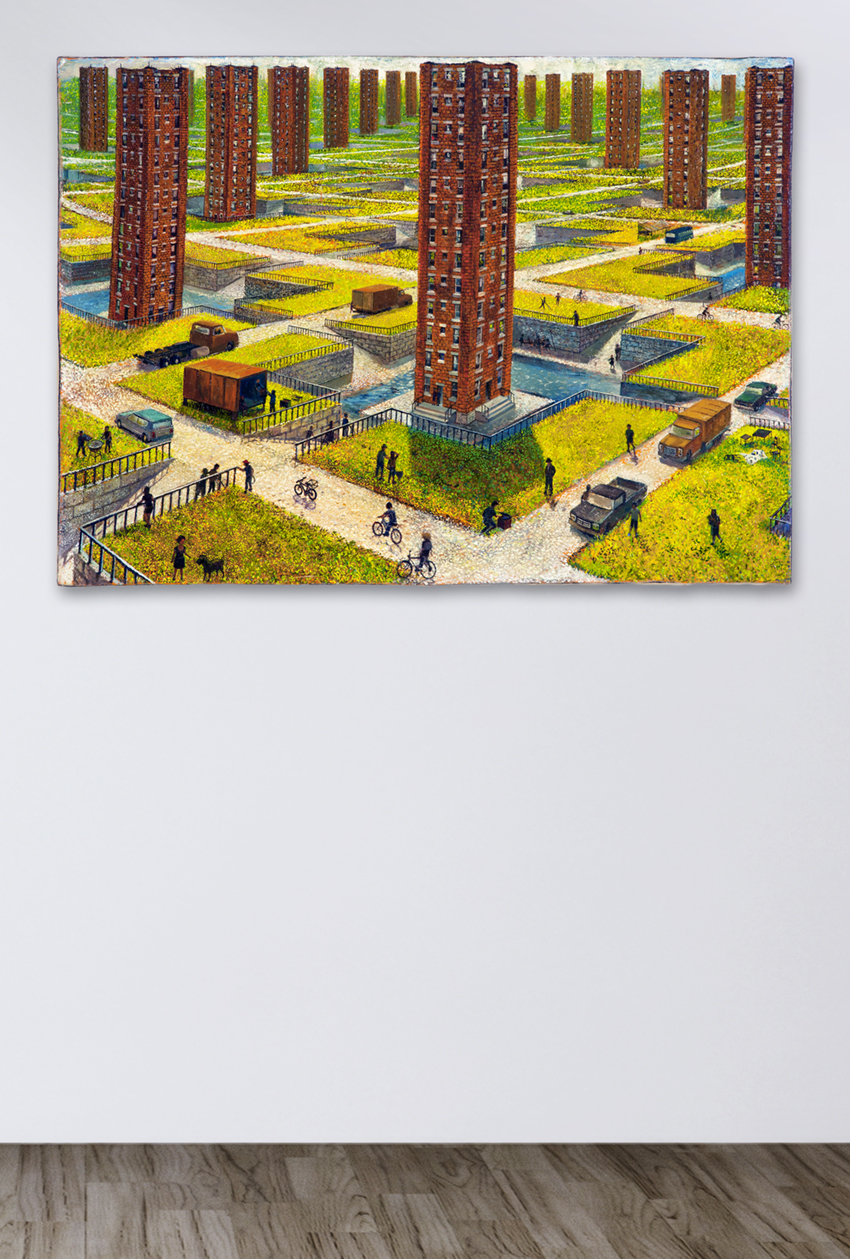

October 20 - November 20, 2022

RYDER HENRY: HOUSING WORKSCLICK HERE for press release

Ryder Henry's work explores an urban future through a lens of the past—views of a future that seemingly has already happened. Vintage cars and bikes line crushed-stone streets, a rocket shell has been converted into apartments, and turbines generate power. Nostalgia is everpresent. A sense of the "salad days." The skies are blue, the grass is lush, and the air is clean and warm. There is a calm that belies the intensity of the environment.

Henry works out these concepts first through sculpture. With an assortment of found cardboard, plastic, and various materials, he creates wonderous housing models based on an obsessive scale of 1: 213.333 and places many of these models in a city he has built in his home (which has nearly outgrown the room). Views of the city inspire the paintings.

In his paintings, he adds life absent from the model city. People here unload trucks, tend to gardens, ride bikes, bar-b-que, and socialize on rooftop decks and patios in an urban architecture that mixes the old with the new (which is also now old).

They offer a glass-half-full view of the future—not your typical Orwellian take. The works show an urban environment that is neither ideal nor oppressive—one that shows an evolution and a future that we can recognize as something not too different from our past and present.

A group of paintings entitled "The Fairgrounds" shows urban-agrarian housing works not dissimilar to Stuyvesant Town but with aquifers. The utopian community concepts are rooted in Le Corbusier's unrealized Radiant City.

Henry grew up in Austin, Texas, but has lived all over the world and his inventive architecture reflects his travels from Texas, Michigan, California, Rhode Island, to France, Lebanon and Cyprus, to where he resides now in Pittsburgh.

Join us for Ryder Henry's inaugural New York City exhibition on October 20, 6-8 pm.

July 14 - September 8, 2022: MANHATTAN BEACH: AN URBAN SUMMER

Steven S. Powers and Joshua Lowenfels have curated an exhibition relating to summer in and around New York City. Also dubbed "Sand, Skin, Sun & Sin," the collection is shown in a salon-style installation with works by James A. Adams, Nek Chand, Henry Ray Clark, Sanford Darling, Frederick Hastings, Charles Jarm, George Morgan, Royal Robertson, John Roeder, LC Spooner, Miroslav Tichy, James W. Washington, Jr., Nat Werner, and a selection of related anonymous works.

The impetus for the exhibition centers around an important collection of "sand paintings" by John A. Adams (1891-1967). Adams, born in Iowa, discovered the work of fellow Iowan Andrew Clemons (1857 - 1894) and was inspired and determined to figure out how Clemons created his art. Adams created detailed works from 1933 that are similar to the style of Clemons, with complex scenes of the Marquette bridge, an American eagle and flag, and a train around a mountain bend with flags from The League of Nations. Adams also "painted" a portrait of Franklin Delano Roosevelt from this period. Then it appears Adams moved to Roseville, California, and worked as a switchman for the Southern Pacific Railroad Company. He had a family and stopped the practice until he retired and resumed creating work in 1965. In his later "sand paintings," Adams worked in a more personal voice with pieces that illustrate two young boys, a large work with portraits of the astronauts Chaffee, White, and Grissom who perished in the Apollo 1 disaster in 1967. The most significant and unexpected work is Adams' magnum opus, which shows a young woman feeding three pigs. The exhibit displays Adams's paper sign that he would bring to state fairs, "SAND PAINTING. The Pictures are made of natural colored sands, and there is NO glue used at all."

In addition, the exhibition features a significant work by Sanford Darling (1894-1973) with swaying palm trees and paintings by additional artists that show waterways, islands, and landscapes. One painting shows an expansive view of Prospect Park, Brooklyn, done by an eccentric artist, Lawrence Rothbort (1920-1963), who worked en plein air and painted with pointed sticks. Works by Miroslav Tichy, The Maine Hermit, Royal Roberson, and anonymous show paintings and sculptures of scantily clad or nude bodies.

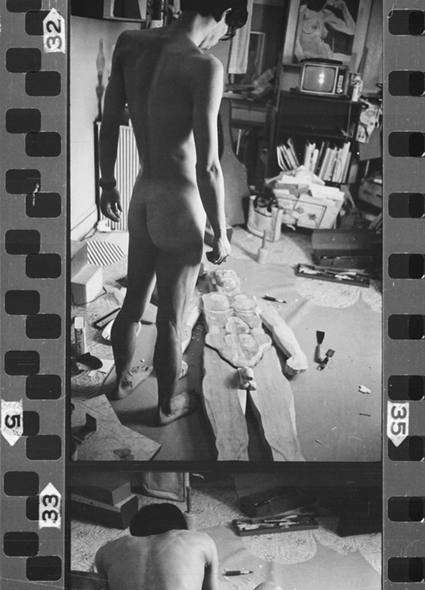

October 21 - November 21, 2021: "Charles Jarm: Bodies of Work"

In the early 1970s, Charles Jarm (1932 - 2021), a gay Chinese-American, lived in New York City on Mulberry Street, where Little Italy and Chinatown overlap. He was nearly forty years old; inspired, he began carving large wooden figures in his living room. The half-sized and full-sized men and women that he carved and constructed were inventive and ambitious. Photographs from the period document Jarm working naked, chiseling the nude wooden subjects flat on the floor of his apartment. Then this remarkable body of work was shelved and, in a sense, put into a time capsule only to be revealed now.

Unfortunately, we know little of Jarm’s life. He was born eleventh of fifteen children to Chinese immigrant parents who moved from Ohio to New York City’s Chinatown to open a laundromat. It is unknown if he had any art instruction. Each figure’s atypical and inconsistent construction makes us believe that Jarm was self-taught in this creative endeavor.

The figures are imposing, confident, and unlike any other figurative works that come to mind. Constructed of lumber-store bought thick pine boards, Jarm carved the figures in shallow relief and sandwiched boards to fill them out and aid in creating hidden joints where limbs are attached. The bodies are further defined with graphite to strengthen and add volume to flat details. Each figure is distinct and likely portraits of friends.

Jarm’s body of work is singular and hard to put into a “school,” though the documentation of him working naked was very much part of the Fluxus movement around him. The act and performance of creating the work appear integral to the physical work itself. Though we do not know the extent to which Jarm was involved in Fluxus, his name appears in The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives at MOMA and lived at a Wooster Street Fluxhouse operated by George Maciunas.

Not only did Jarm reside where Chinatown and Little Italy overlap, but his love life also mirrored it. His lifelong partner was an Italian-American named Rocco Sacramone, a music executive with CGC Records. It appears that after these years of mid-life creativity, he had a career in the daycare business and then retired to Palm Springs with his partner, where he stored the work for the last fifty years.

Jarm must have been certain that he created something solid with his inspired “Bodies of Work,” however, due to unknown circumstances, the works were never shown, time and life moved on, and the moment was lost. Timing can be a fickle mistress. Maybe the work was too against the grain, as it were for the time. It was objectively good and unlike any other sculpture around him in the Downtown art scene, which was more abstract and conceptual. In a sense, it was more like the portraits being painted by Chuck Close, but on a more personal scale.

We are honored to mount this “Bodies of Work” exhibition of Charles Jarm’s work and give him a posthumous spotlight.

September 9 - October 17, 2021: "Selections From The Peter Brams Collection of American Folk & Outsider Art."

Peter Brams has been a collector all his life. A voracious collector! In the 1980s, while still in his thirties, he was ahead of the curve collecting works by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Gilbert & George, Carl Andre, and Philip Taaffe. By the late 80s, Brams engaged in the works of William Edmondson, William Hawkins, and Sam Doyle.

In the early 90s, Brams had the courage and gumption to dive fully into American Folk Art and seek anonymous works. He felt great art needn't have a name attached to it—just the eye of a confident collector.

During this decade, he vacuumed up left-of-center 19th-century folk art and created a legendary collection (later sold at auction in 2001). Its scope was broad in one sense and highly targeted in another. Brams' openness and knowledge of art history enabled him to see beyond the conventional and appreciate objects often challenging and sometimes overlooked by more mainstream collectors. Everything he acquired had a particular quality of vision, execution, and historic surface.

What Brams learned through antique art was that time could impart its stamp on a maker's work and often improve it. With patination from use, age, and often exposure to the elements, time could enhance the integrity of the surface—make it complex and richer beyond its original state. This obsession with surface and an economy of line led Brams to form an important collection of Woodlands Indian Art.

Since selling his Woodlands collection ten years ago, Brams has revisited his love of American folk sculpture and painting.

The selections chosen for the Powers & Lowenfels exhibition reflect this return focusing on the human form encompassing works in stone, wood, concrete, and mixed media and will be integrated with choice examples from our inventory.

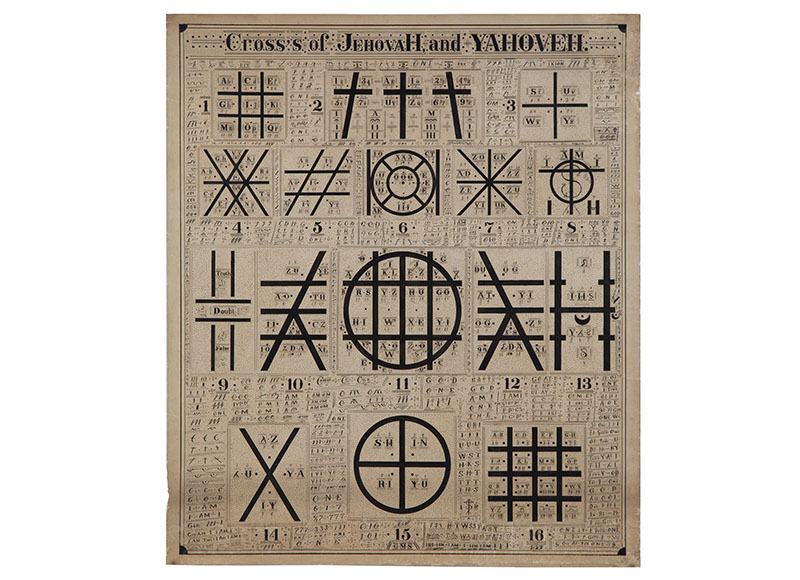

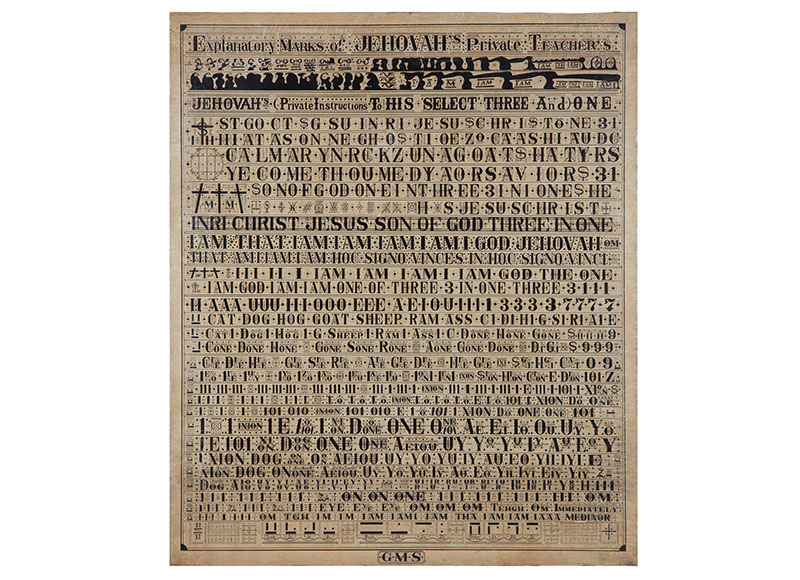

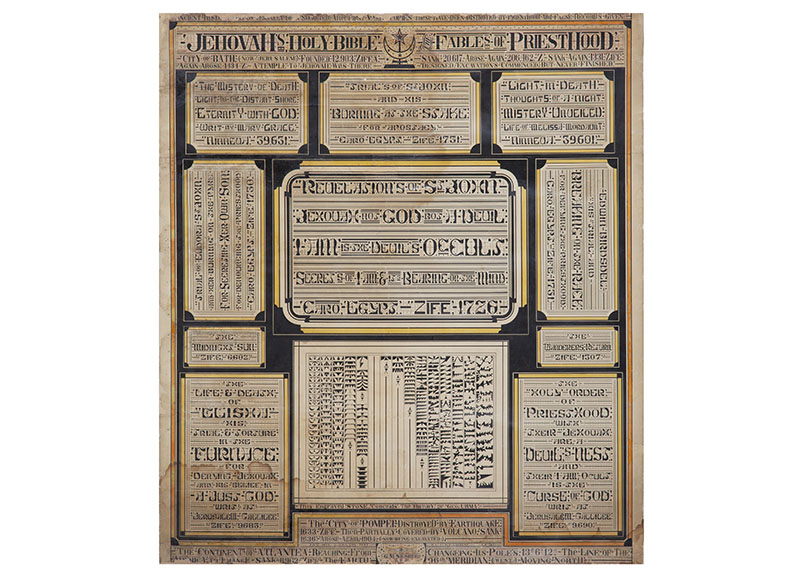

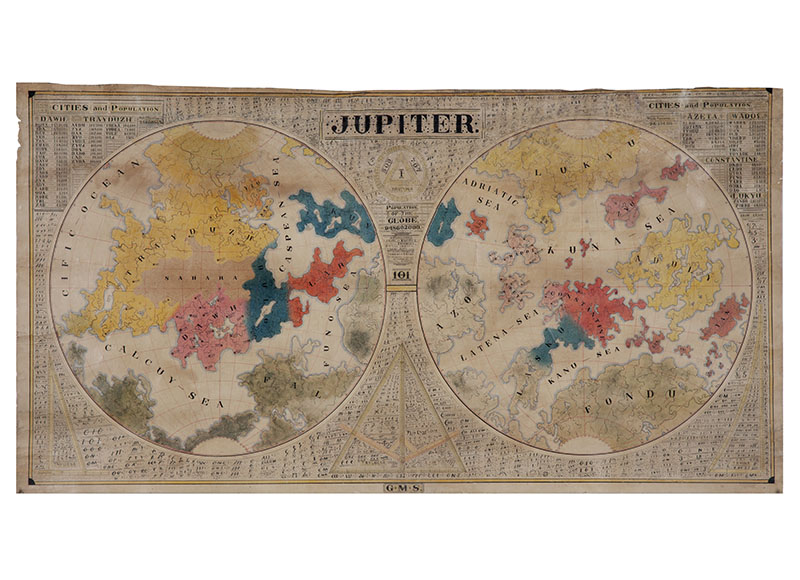

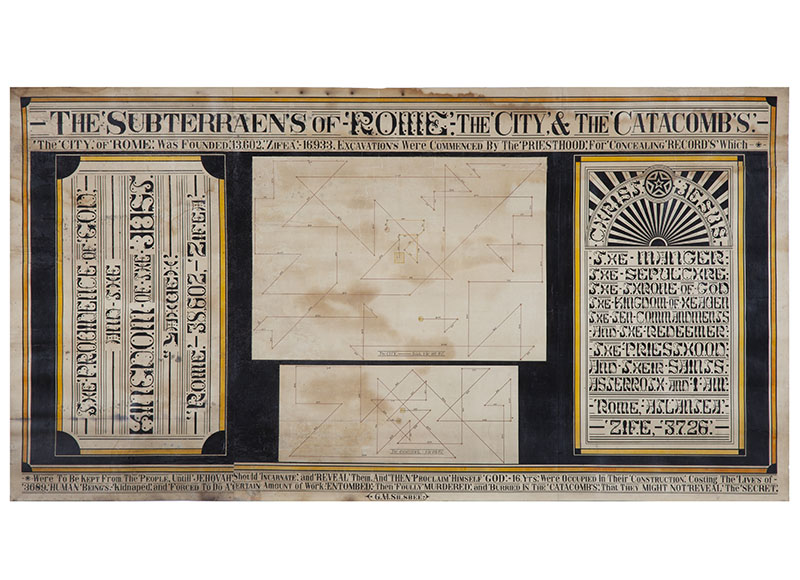

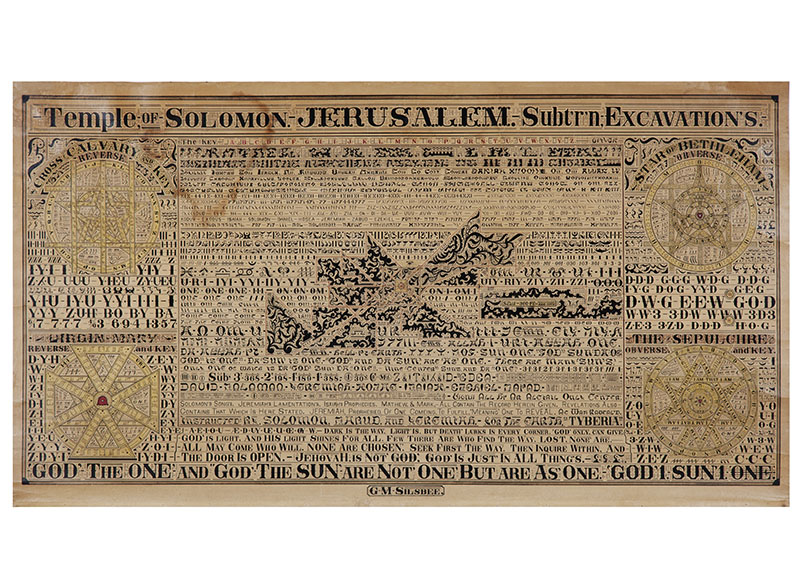

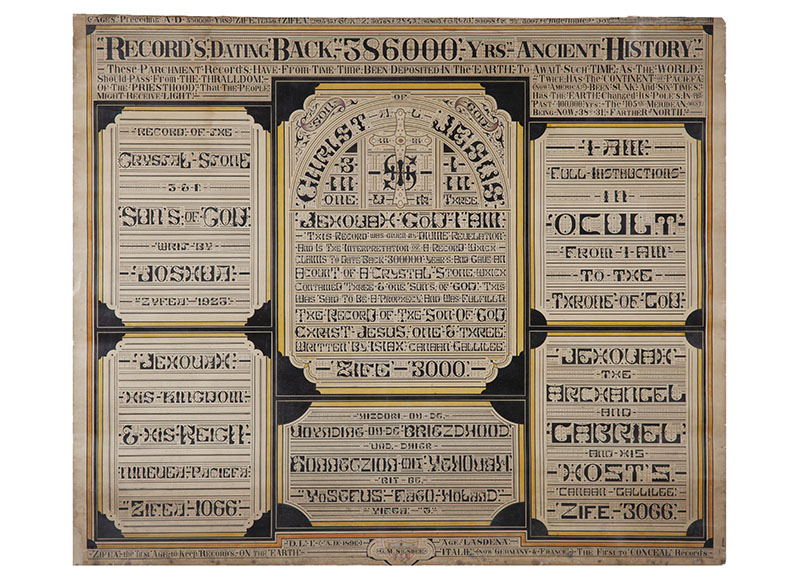

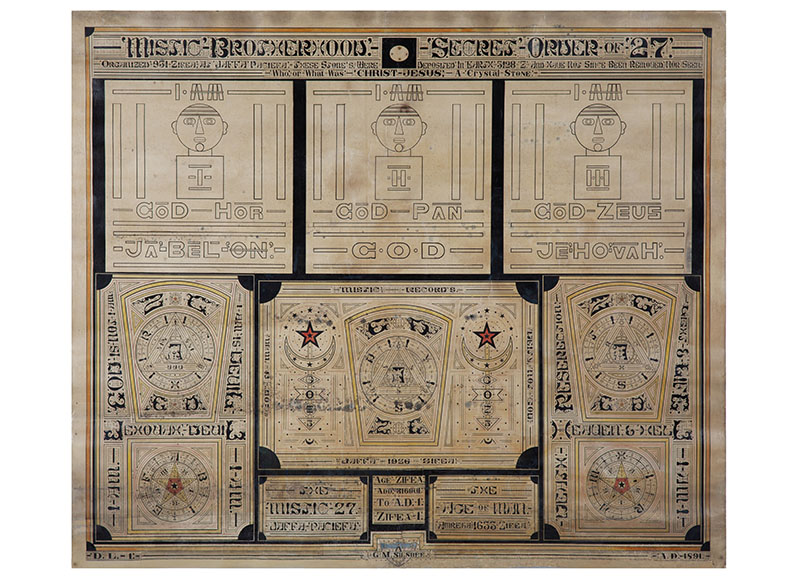

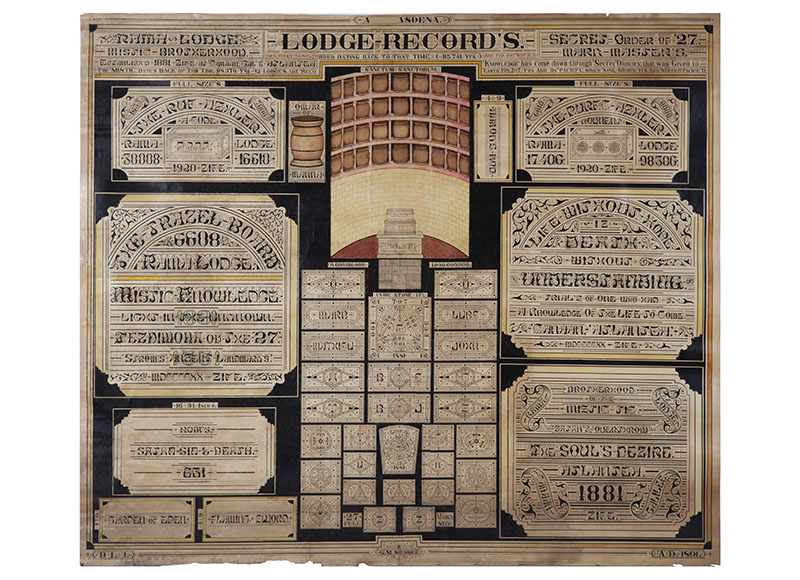

January 28 - March 13, 2021: Explanatory Marks: The Mystical Drawings of George M. Silsbee.

CLICK HERE for PDF of essay and higher resolution images

Steven S. Powers and Ricco/Maresca Gallery present, Explanatory Marks: The Mystical Drawings of George M. Silsbee. This collection of nine large-scale drawings, created in 1891, examine Freemasonry, Mysticism and the Occult. This sold out exhibit ran from January 28 - March 13, 2021.

At different points during his life, George M. Silsbee was an artist, miner, engineer, and organ builder. But like many men in the second half of the 19th century, he also had a mystical alternate identity where ceremony, rites, and a mastery of secret symbolism connected him to something greater than himself. In his Masonic practice, he was a seer of rituals and conjurer of archaic wisdom, translating divine guidance into labyrinthine charts. Over a century since they were created, his works on paper—now exhibited to the public for the first time—offer a tantalizing vision to be untangled. Their dense networks of ink and watercolor calligraphy, encoded text, illustrations, and numbers—where no space for symbolism is wasted—suggest that with the right understanding one could journey through their protocols to ancient esoteric knowledge.

The known details of Silsbee’s biography, gleaned from census records, city directories, fraternal society publications, and newspaper archives provide just a spare sketch of the artist. Born on January 9, 1840, in Oneida County, New York, he died on his birthday in 1900 at the age of 60 near Waukau, Wisconsin. His obituary called him an “artist of ability”—although the medium of art is unspecified— and noted that he’d arrived in Wisconsin with his parents as a child in 1845 and later moved to Summit in Waukesha County. During the Civil War, he served three years in the First Wisconsin Cavalry and then in the 1870s relocated to Denver, Colorado. There he worked with organ builder Charles Anderson on an instrument with over 500 pipes, making it one of Colorado’s largest pipe organs. Then he moved on again, this time to the newly bustling Leadville, a major mining center of the Colorado Silver Boom, and spent two decades working as a miner and engineer.

In 1875, Silsbee was listed as a member of the Kenosha Masonic Lodge, No. 47 in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and it was during his years in Leadville that he embarked on the Masonic art that his family would call “his life’s work.” The mounting of the paper charts on linen with wooden dowels suggests they were meant to be unrolled and displayed, yet they were passed down in his family for four generations rather than being part of a Masonic lodge. Still, the square and compass that appear on a shield behind Silsbee’s signature on three of the charts—stonemason’s tools that are the most recognizable symbols of Freemasonry—affirm his work as that of a Masonic artist.

By the time Silsbee created these pieces at the end of the 19th century, the iconography and symbolism of fraternal societies had become largely standardized through the mass production of paraphernalia. Whereas the majority of fraternal society objects in the 18th century were crafted by local artists or were homemade, the huge boom in 19th-century membership led to a mail-order business for costumes, banners, décor, and anything else needed to turn a clubhouse in an ordinary American town into an occult temple to higher truths. While Christianity and the Bible were often at the center of these societies’ systems, they had an added theatricality through an appropriation of the ancient and “exotic” drawing in Victorian architectural and art movements ranging from Egyptomania to Moorish Revival. Silsbee’s experience as a Civil War veteran and worker in a rapidly industrializing society would have been akin to many of his fellow members who sought a community that was also an escape from modern life and its responsibilities.

Silsbee’s work in its style stands apart from other Masonic art of the late 19th century. Degree charts and paintings were common in Masonic lodges, however, they tended to be figurative with allegorical scenes and vibrant symbols. Aside from a stylized map and an illustration of an inner sanctum, Silsbee’s charts are mainly ink on paper and only have a few figurative elements amid the stark typography and shapes. A small all-seeing eye overlooks a network of calligraphic flourishes; three abstracted faces stare out from the text announcing the names of the gods Jabulon (a uniquely Masonic term believed to represent a secret name of God), Pan, Zeus, and Jehovah, as if linking them all to one divine power.

In the cryptic text and symbols, his charts are more similar to Masonic ritual books than other forms of fraternal art. These publications were mnemonic aids for candidates learning the initiation ceremonies that would allow them to progress through degrees. To an outsider, the writing in these books looks like nonsense as its reading relied on an existing understanding of Masonic information, with the shorthand and symbolic prompts intended to help with memorization and personal study. Like Silsbee’s work, these books offered a way to ruminate on knowledge while upholding the candidate’s oath to “not write, print, paint, stamp, stain, cut, carve, hew, mark, or engrave” any Masonic secrets.

Examining each of Silsbee’s works is like focusing on something through a microscope, every approach revealing more and more detail that contributes to a greater comprehension of the whole. The incredible depth and variation of symbolism, from rune-like forms on the “Cross’s of Jehovah and Yahoveh” to the pigpen cipher key embedded at the top of “Temple of Solomon. Jerusalem. Subt’rn, Excavation’s,” show a deliberation where every mark is imbued with meaning. They include fragments of narratives referring to the Bible and the classical world, from records hidden in the Roman catacombs to the destruction of Pompeii, sometimes evoking subjects that would have been expressed in Masonic rituals, such as the “flaming sword” and its guardianship of the Garden of Eden that was frequently represented in Masonic lodges as a weapon with a wavy blade. Abstract patterns reminiscent of semaphore flags, signaling something to the viewer in their shapes that transform like an animation in parts, appear in a chart for “Jehovah’s ‘Holy Bible’,” while on “Temple of Solomon” the Star of Bethlehem is interpreted an otherworldly celestial presence with a lattice of intersecting lines, adorned with a rhythmic motif of dots and words.

Even without understanding the exact intentions behind each element of these works, it is easy to get pulled in by the repeating of phrases and characters that Silsbee used to build these pathways to knowledge of something ancient and spiritual. Moving through the scripts of “Explanatory Marks of Jehovah’s Private Teacher’s,” where black curls of ink and ciphers add to its aura of deep meaning, the phrase “I am” emerges again and again like a mantra: “Christ Jesus Son Of God Three In One I Am That I Am I Am I Am I Am I Am I God Jehovah ... I Am God I Am I Am One Of Three 3 In One.” It goes on and on, letters interrupted by numbers, symbols, and combinations that resemble equations. A textural pattern of tiny dots joins it all so you can almost hear the meditative tap of Silsbee’s hand reverberating through each line, trying to find a way to communicate sublime mysteries whose complexity could not be expressed by terrestrial images.

We are now witnessing these works far from their original context, not knowing the specific rite they were designed to guide, or the contemplation they were meant to inspire for those who understood the shared secrets. It is also possible we are only seeing part of a larger body of work that Silsbee created in his attempt to make the mystical into something navigable for those who were dedicated to learning. Now that Silsbee’s work has come to light, there is an opportunity to consider its intricacies as well as broaden the appreciation for the breadth of 19th-century fraternal art. Although it was likely made for clandestine purposes—to be engaged with by the select members of these groups—this art speaks to the human drive to connect with something sacred, to feel part of a long thread that through stories and rituals links us to the past. In these puzzles of symbols and words, much of Silsbee’s intentions remain enigmatic, but in exploring the obsessive patterns and ornate texts there is a powerful experience accessible to anyone who takes the time to look closely and let themselves be transported.—Allison C. Meier, 2020.

STEVEN S. POWERS • 53 STANTON ST, NY, NY 10002 • 917-518-0809 • email: steve@stevenspowers.com • © all rights reserved