- HOME

- INVENTORY

- GALLERY

- BOOKS

- CATALOGS

- ABOUT & MORE

- CONTACT

Contact Us

George E. Morgan (1870-1969): Memories of the Kennebec

***FOR WORKS AVAILABLE BY MORGAN, PLEASE GO TO THE PAINTINGS AND PAPER GALLERY PAGE***

Mapping has occurred across time and cultures and the ability to map, to express in material form the cognition of large-scale environments from wholly or partially aerial perspectives, is indeed a cultural universal. -David Stea, James M. Blaut and Jennifer Stephens Mapping As A Cultural Universal

In 1962, the town of Hallowell, Maine was celebrating its 200th birthday, or bicentennial. A commemorative book was commissioned and printed, documenting its rich and industrious past—events were planned and banners put up. Nearby in the town of Gardiner, surely inspired by the locale fanfare, a resident nearly half as many years old, put brush to canvas and recorded his recollections of a time when the towns of Hallowell, Gardiner, Randolph, and other mill towns of the Kennebec River were vital exchanges of the Maine economy.

The Kennebec River was first explored by Samuel de Champlain in 1604 and then settled in what is now Phippsburg, Maine by the Popham Colony in 1607 (the first English attempt at a colony in New England—it was abandoned one year later). Providing passage from the Atlantic coast to the Maine interior at Moosehead Lake, the Kennebec also provided a plenitude of anadromous fish (Atlantic salmon, alewives, shad, sturgeon, and striped bass) and loads of water-power, which was ideal for livelihood, commerce and trade. Consequently, over the years, the towns of Bath, Gardiner, Hallowell, Augusta, Waterville, Skowhegan and many others were settled. By the power of the river's falls to the north and with the introduction of a dam in 1839, the towns along the Kennebec, south of Augusta, became thriving mill towns producing and exporting granite, paper, timber, ice, shoes, and textiles. Throughout the nineteenth century in Maine, these industries, including shipbuilding, provided employment and a prosperity that was second only to the commerce of Portland. It is hard to imagine now, but the populations of Hallowell and Gardiner in the nineteenth century were larger (slightly) than what they are at present. With the advent of electricity, competition from other centers of industry, and cheaper means of production, the shipbuilding and mill industries of the Kennebec River dwindled and eventually all but vanished.

On October 9, 1870, George Eugene Morgan was born to George William and Vesta Rowena Farnham Morgan of Chelsea (three-and-a-half miles east of Gardiner). As a young man and as most in the area, Morgan found work along the Kennebec, first in Augusta with a furniture maker, then for many years as a harness maker, and then for even more years he worked in the shoe factories of Gardiner (Commonwealth Shoe Company and then the R. P. Hazzard Company). He was ranked a sergeant in the Maine Militia, and when World War I broke out, Morgan, already 47, was deemed too old for service. He married twice and had five children.

In the spring of 1962, Morgan was 91 years old and living in a rest home in Gardiner. Morgan was not one to sit idle, and though sketching on paper and cardboard occupied him for some time, he ached for something more. Word got out, and apparently through some connection at the home, Morgan was introduced to a local folk art and antiques dealer, Anne Wardwell of Farmingdale. When Wardwell met Morgan, she must have seen something that inspired her. In the words of Howard Rose, from Unexpected Eloquence, "Mrs. Wardwell seems to have had one of the great prophetic eyes in dealerdom." Wardwell became his benefactor - or more so his enabler - providing him with brushes, paints, turpentine, and canvas boards. Over the next 18 months, Morgan created twenty-plus remarkable memory paintings.

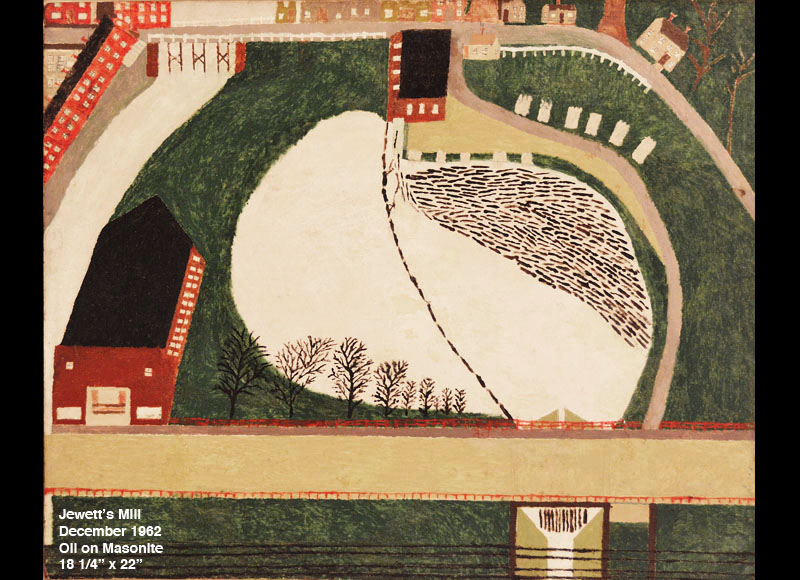

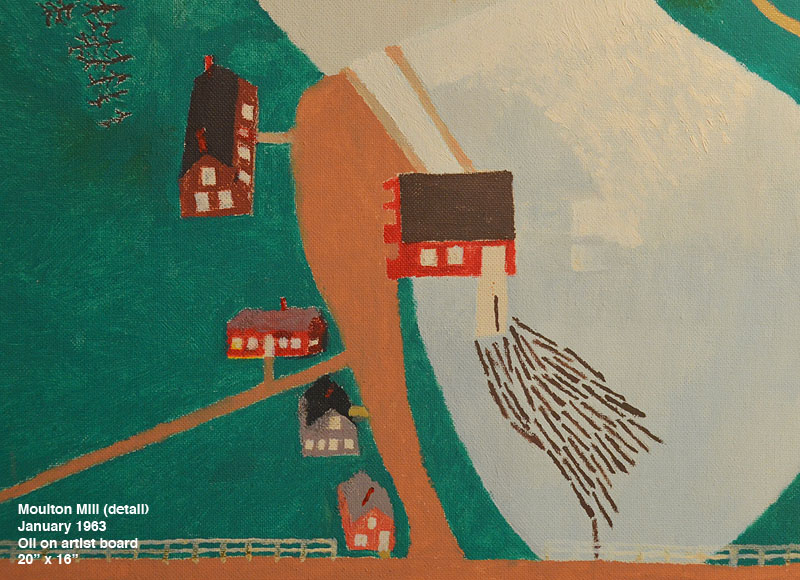

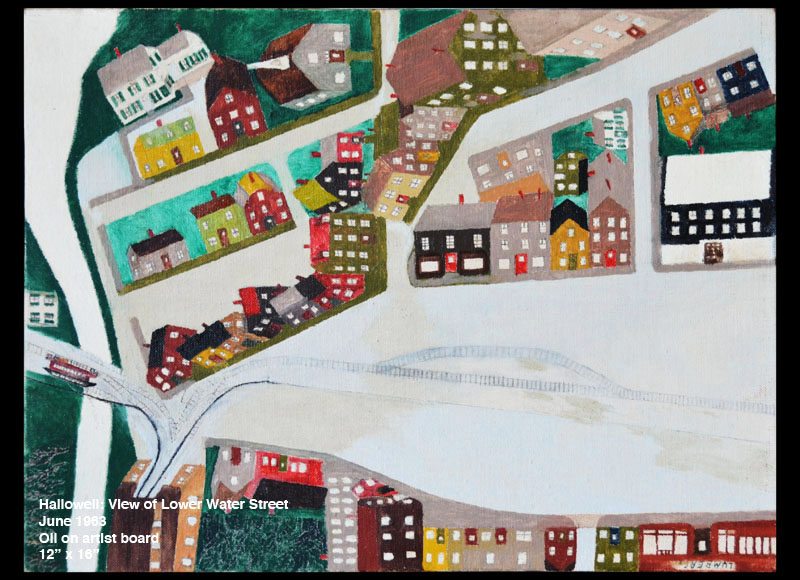

The body of Morgan's work is best - and most often - described as "map-like." His townscapes and depictions of local landmarks are often seen from overhead and/or from a high-vantage point. They provide for us, almost literally, a road map of these towns as they were at the turn of the twentieth century. The three works, Hallowell: View of Lower Water Street, Freshet 1923, Bridge Dividing Kennebec River, done in a flourish in just two months (June and July 1963) are arguably his most complex, finest, and accessible works. In each, Morgan precisely tries to work out the perspective (a ruler was always at hand); however, it is never (academically) correct. In the essay, "Mapping as a Cultural Universal," the authors assert that "to communicate...mapmakers distort...distortions from accepted veridicality may be the result of attempts to increase the map's informational value." Though Morgan's unconventional perspective is incorrect, it is more informative—showing us spaces and details of buildings that we would not otherwise see.

George Morgan had an energy and persistence that belied his age; however, he was mortal. At 94, he called it quits. Morgan lived to 99 and died in Augusta, Maine in 1969.

Early on, Morgan's paintings garnered attention and demand. Correspondence shows that Anne Wardwell displayed the works and sold one in October 1963 to the prominent art collectors, Edith and Ellerton Jette of Sebec, Maine (another note states that she was to contact them if ever she wanted to sell the entire collection). After Morgan's death, Wardwell maintained the collection until the mid 1970s, when she sold all of Morgan's work to collector friends in Connecticut. From their hands to another in New York, and then another, they found themselves with the pioneer folk art collectors Howard Rose and Raymond Saroff. Upon a visit to Rose and Saroff, the then-director of the Museum of American Folk Art (now the American Folk Art Museum), Robert Bishop called out, "There they are! You've got them!"

George E. Morgan's work is well represented and discussed in the landmark book, "Unexpected Eloquence," by Howard Rose and in Folk Art Magazine, George E. Morgan: Self Taught Maine Artist, by Chippy Irvine, Summer 1998.

Morgan's body of work has been exhibited at: The Playhouse, Boothbay, ME 1963; The Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, ME, "George E. Morgan: Self Taught Painter of Maine" July 16 - October 11, 1998; and The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, Chicago, IL, "George E. Morgan: Maine Streets" February 5 - April 10,1999.

STEVEN S. POWERS • 53 STANTON ST, NY, NY 10002 • 917-518-0809 • email: steve@stevenspowers.com • © all rights reserved